Dora Rodriguez is one of my favorite people. After spending an entire day together in and near Sásabe, Sonora, Mexico, Dora invited me to join her and a group of friends again, this time on a trip to Yuma. The trip had a few goals: to see the wall and the border in Yuma, to meet with Dora’s friends Fernando and Nathalie there and witness to their work, to deliver supplies to Fernando and Nathalie, and to introduce these friends and places to three other friends of Dora plus myself. Our fearless traveling companions included Sister Judy, a badass feminist nun; a young man named Isaac whom Dora sponsored out of immigrant jail; and his girlfriend, who also volunteers at Casa de la Esperanza.

Isaac immigrated from the aptly named Guerrero (warrior) state in Mexico, which is controlled by numerous cartels. Upon entering the U.S., Isaac, like most single young male asylum seekers, was thrown in immigrant jail. To get some fresh air and exercise while he was there and to relieve himself of intense boredom, Isaac cleaned the facilities for $1/day. Over time, Isaac made friends with other detained migrants who also cleaned in other parts of the facilities, calling to each other from the patios. One day one of them threw a rock to Isaac with a message wrapped around it simply stating: “Dora [and her phone number]. Call her, she will help you.” So Isaac did. After piles of paperwork and financial and security background checks, Dora was able to sponsor Isaac out of immigrant jail. She now refers to him as her adopted son.

Isaac’s mother, brother, and sister were still in Tijuana when I met Isaac. His young sister had been befriended by a much older man, who gave her drugs and jobs. When we learned of those details, markers of human trafficking, Dora immediately contacted friends who run a shelter at the border in Nogales, Sonora. With the financial support of Dora’s organization, Salvavision, they were able to get Isaac’s family into a safe house, off the dangerous streets of Tijuana. Just a few weeks later at the shelter, Isaac’s family has an appointment with the new CBP One app to present themselves at the border on March 3rd!!

As we arrived in Yuma, Border Patrol was loading the last of a group of migrants onto a bus. We were met by Fernando and Nathalie, who both work for AZ-CA Humanitarian Coalition serving and advocating for migrants at the border near Yuma. Until very recently, the border crossing in Yuma had no shade, no toilet facilities, no drinking water, and no garbage dumpsters. Border Patrol systematically confiscates all bags and other belongings from migrants, and simply threw them in piles. Whenever a Republican politician was scheduled for a photo op or press conference in Yuma, they would suspend garbage pickup at the border, deliberately letting the things that Border Patrol had seized from migrants pile up in trashy heaps, only to blame the migrants for the mess.

Thanks to the tireless work of Fern and Nathalie, there are now two large trash dumpsters at the crossing. Border Patrol continues to confiscate and toss migrants’ meager belongings, but at least now they are contained in a more sanitary manner. AZ-CA’s advocacy has also compelled Border Patrol to provide a shade shelter where migrants wait—sometimes for hours—for BP buses to take them away. The dumpsters and shade are joined by portable toilets, and even drinking water. Such basics of human dignity, finally provided due to the advocacy of fearless young people.

Together with Dora’s friends, we witnessed many gaps in the border wall here as well. Huge sections of wall had to be removed at great cost to taxpayers because they were built illegally on sovereign Native American lands. The Colorado River, which forms the border between Arizona and California, flows through Yuma. We saw the canal where Mexico’s share of the water is diverted from the Colorado River. And we all enjoyed a lively lunch together, learning more about the work each of us does serving migrants.

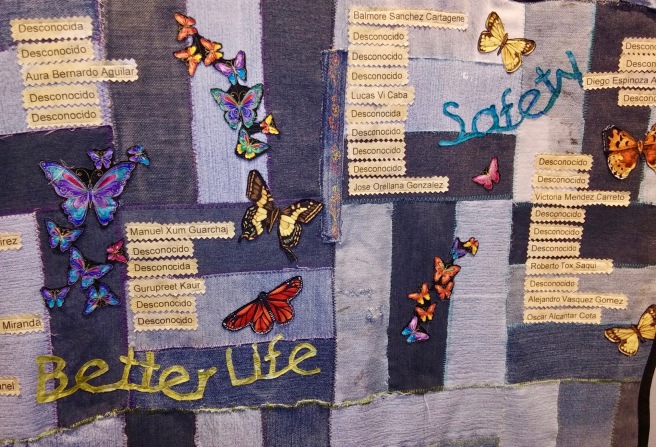

In addition to the two days I spent with Dora, she also recommended my visit to the Migrant Quilt Project, which memorializes the thousands of migrants who have died in the Arizona desert. I recently posted a slideshow of the exhibit on this blog. Dora further recommended Tom Kiefer’s photo exhibit El Sueño Americano (The American Dream), which is showing in Ajo, AZ. Kiefer documents migrants’ personal belongings that were seized and discarded by CBP. I didn’t get to the exhibit, but you can view it here: https://www.tomkiefer.com/el-sueno-americano. I highly recommend it. I also added several books to my reading list thanks to Dora’s and others’ recommendations. Dora is a wealth of stories and wisdom, and a gift to the border community. You can support Dora’s work here: https://salvavision.org.

While in Tucson I had hoped to spend a day with Alvaro Enciso, planting crosses in the desert at the sites of migrant deaths as part of his Donde Mueren los Sueños (Where Dreams Die) project. Alvaro’s team members spent two days scouting the chosen locations for a way in, but the sites were so remote and wild as to be inaccessible, so the trip was cancelled. You may read about my previous trip with Alvaro here: https://wordpress.com/post/stand4welcome.wordpress.com/5070